1 | Childhood in Fez

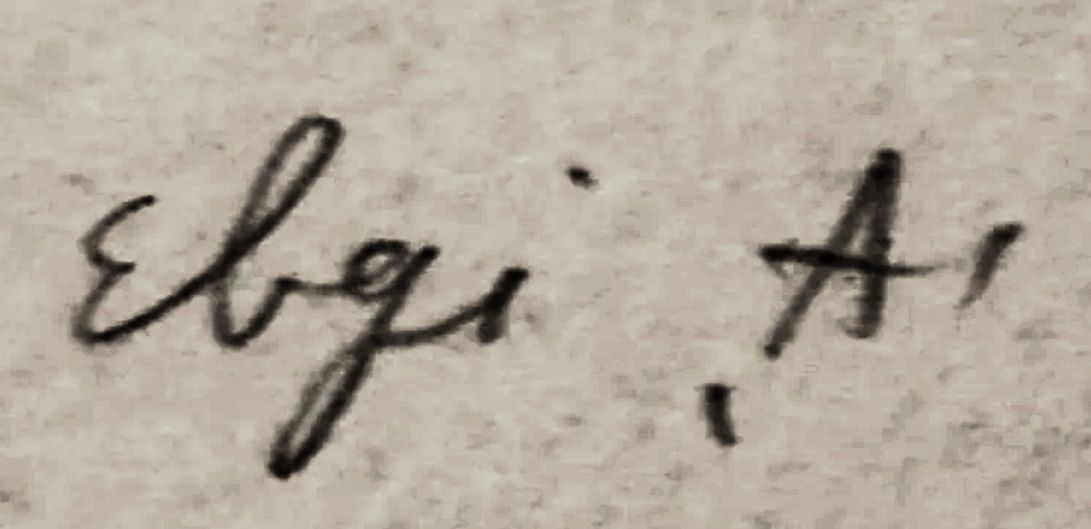

Amram Ebgi, an artist and printmaker, was born in Fez, Morocco, in the summer of 1939. Entering the world as an old-world immigrant during a period of imprecise record-keeping, his exact birth date is unknown, though it is officially recorded as July 16, 1939.

Amram's early years in Fez were deeply influenced by his life withOrthodox Jewishparents. They strictly followed Jewish traditions, and the community as a whole was committed to spending considerable time praying and studying the Torah. The majority of the Jewish community in Fez were descendents of Spanish Jews who had settled there after fleeing Spain in the 15th century.

When he was a child, as Amram recounts, his father would beat him for missing Torah study or appearing lax in prayer. Therefore, it was with profound relief and anticipation that he seized the opportunity to leave Fez and begin a new life in Israel at the age of 12.

2 | Aliyah to Israel

In 1951, Amram's move to Israel was facilitated by the internationalYouth Aliyah,a peace organization founded during the Holocaust with the mission of rescuing Jewish youth from the atrocities of the era.

Post-Holocaust, the organization expanded its reach into North Africa to aid Jewish children like Ebgi in Morocco, who were given opportunities for a life in the recently established state of Israel.

Amram discovered his new home inKfar Blum,a kibbutz located in Israel'sUpper Galileeclose to the Lebanese border. At the kibbutz, he deeply engaged with the community, pursued Jewish studies, and learned both Hebrew and English.

3 | Art Career Beginnings

From a young age, Ebgi began drawing solely for his personal pleasure. Amram began his art career officially in 1954 when he was 15 years old. Thanks to a scholarship1, he was able to spend time at theAvni Institute,where he studied underYehezkel Streichman.Later, Amram studied ceramics underAharon Giladi2.

Back at the kibbutz, he arranged for funding to establish an art studio where he dedicated his time. His first solo exhibition took place inKiryat Shmonain 1961.

In the years that followed, Amram's parents, three sisters, and two brothers followed him to Israel, joining a significant wave of Jewish emigration from Morocco.

As Amram's talent became more recognized, arrangements were made for him to relocate to America to further nurture his potential. Kfar Blum facilitated his move, and in 1969, Ebgi settled in New York City.

However, before moving to America, his art career hit a brief pause when he became involved in the1967 Arab-Israeli War,serving as a paratrooper, receiving multiple commendations, and sustaining injuries in combat3.

4 | New York City Education

Upon arriving in New York City, Ebgi took classes at theBrooklyn Museum Art School,while simultaneously establishing a base to further refine his craft. Later, he dedicated his time at thePratt Graphics Center,a former workshop and artist hub associated with Pratt Institute, specializing in traditional printing techniques. The center, previously located at831 Broadway in New York City,closed in 1986.

At the Pratt Graphics Center, Ebgi participated in the printmaking community and honed his early techniques inintaglio printmaking,a method that particularly captured his interest and affection.

Ebgi primarily employed theetching technique,which involves using an acid bath to create grooves on the exposed areas of a copper plate's surface. Additionally, he produced prints using therelief method,where ink is applied to the raised portions of a plate.

He also produced a handful ofwoodcut prints. Over his career, he crafted hundreds of intricate copper plates using these methods. Pace Prints, which is not affiliated, offers a comprehensiveglossary of printmaking techniques.

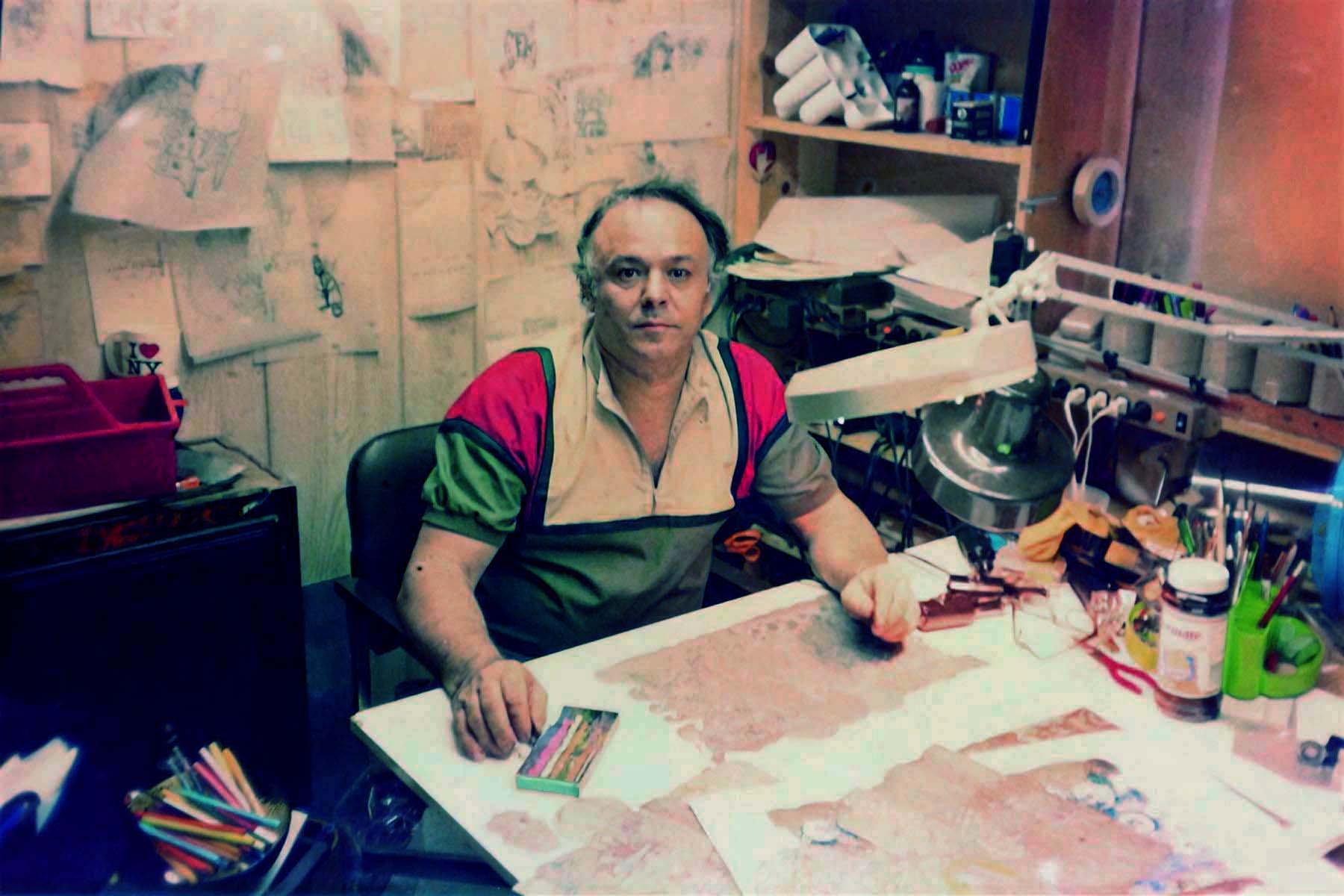

Ebgi quickly commercialized his education by setting up a studio in his Queens apartment onMetropolitan Avenue,equipped with an etching press for producing works for sale. As his business grew, he invited his youngest brother from Israel to help with the printing process. However, the collaboration did not last long, and Ebgi soon returned to working alone.

5 | Rockville Touring

In the 1970s, Ebgi toured extensively, presenting his artwork at numerous art fairs and local Jewish Community Centers across the United States. In 1974, he married and established a base inRockville, Maryland.

While in Rockville, Ebgi became known for hosting open houses where he displayed his artworks throughout his home and outdoors, selling to passersby on the street. He gained recognition in the Rockville art community, and multiple profiles of Amram and his work were featured in the local Rockville press.

6 | New Miami Base

In 1981, Ebgi made a significant move to Miami, Florida, where he established an art studio. He went on to achieve remarkable success, holding solo exhibitions across the USA and Israel. Amram's art was featured in various major exhibitions, including several apperances at New York Art Expo, now operating asArtexpo New Yorkand South Florida'sCoconut Grove Arts Festival.

By the late 1980s, Amram had amassed considerable wealth and constructeda large houseon the shore ofSky Lakein North Miami Beach, Florida, where he also contributed to the design. The property was distinguished by its distinctive appearance: the exterior looked like a place of worship, while the interior was like a museum.

7 | Recognition & Impact

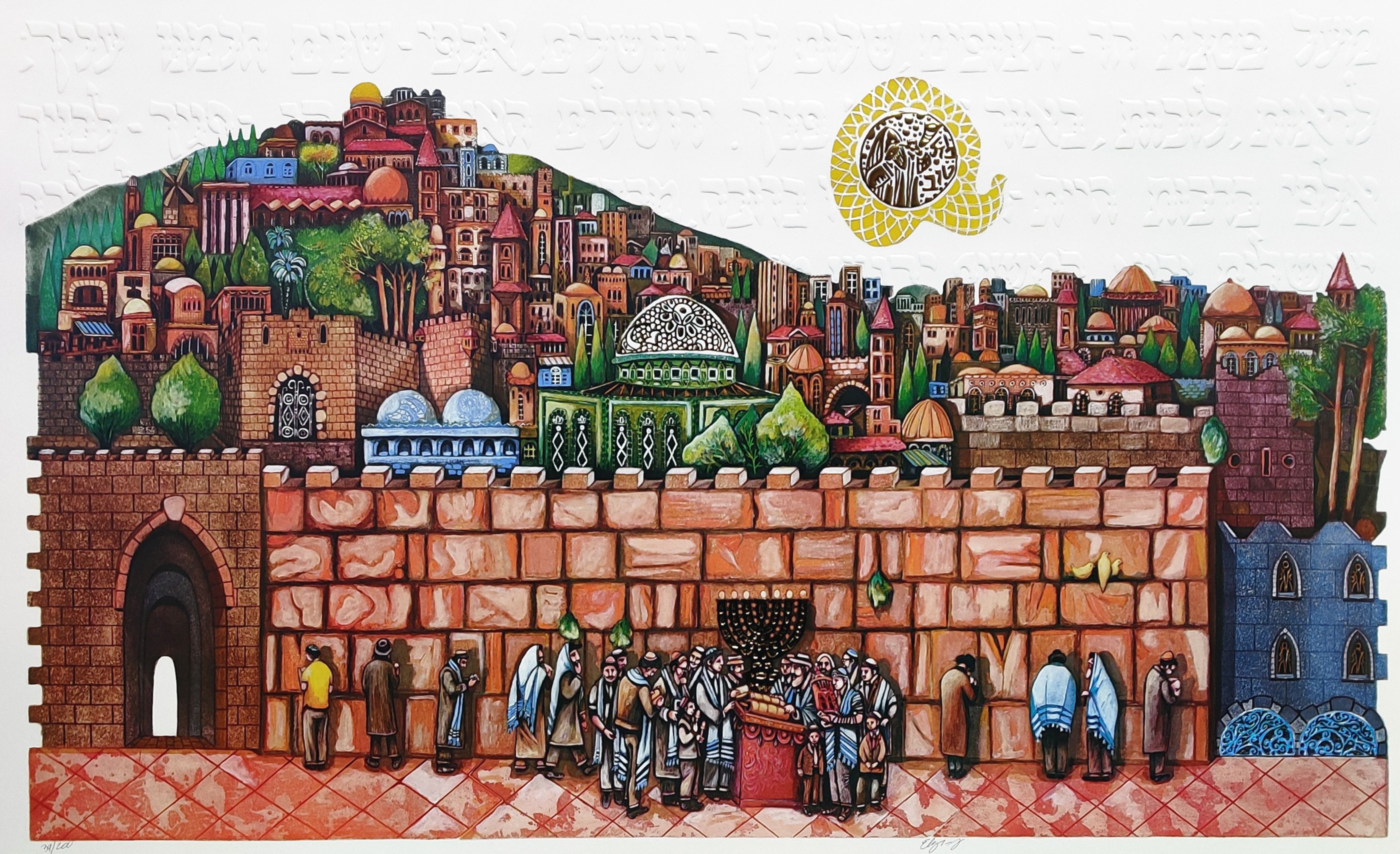

Ebgi's talent was acknowledged by prominent figures likeEhud Olmert,then Mayor of Jerusalem andPresident George H. W. Bush,then Vice President of the United States.

The exact count is unclear, but it's estimated that Ebgi's artworks, which probably exceed 100,000 individual sales including retail and resale, decorate living rooms throughout the world in the homes of both Jewish and non-Jewish families. His works sometimes appear in the background of well-known publications, including a2023 New York Times profile of Dr. Ruth.In the primary photo of the article, two of Ebgi's artworks are visible above Dr. Ruth's left shoulder.

He could be a meticulous technician, skillfully converting his ideas into paintings. Ebgi's legacy remains strong. His creations continue to be appreciated, with his vibrant and multifaceted prints resonating on both historical and modern levels. Undoubtedly, Ebgi offers a glimpse into a distinctive artistic vision that harmoniously blends Jewish traditions with innovative expression.

8 | Onset of Illness

In his later years, Amram Ebgi, once celebrated for his remarkable artwork, encountered significant difficulties. The precise reasons behind Ebgi’s cognitive decline remain unclear, but it is suspected that it was linked to his extensive use of a prescription drug namedCylert,a medication whose approval was eventuallywithdrawn by the FDA.

Additional factors may have played a role, including prolonged exposure to hazardous chemicals used in printmaking, potential genetic predispositions, and possibly unhealthy mental health practices. The exact cause remains a mystery.

Regardless of what caused the illness, Ebgi's artistic talents, once showcased in his exquisite creations, began to deteriorate. His works, which were once highly regarded and sought after, started to display a noticeable decline in quality and attention to detail.

9 | New Artistic Direction

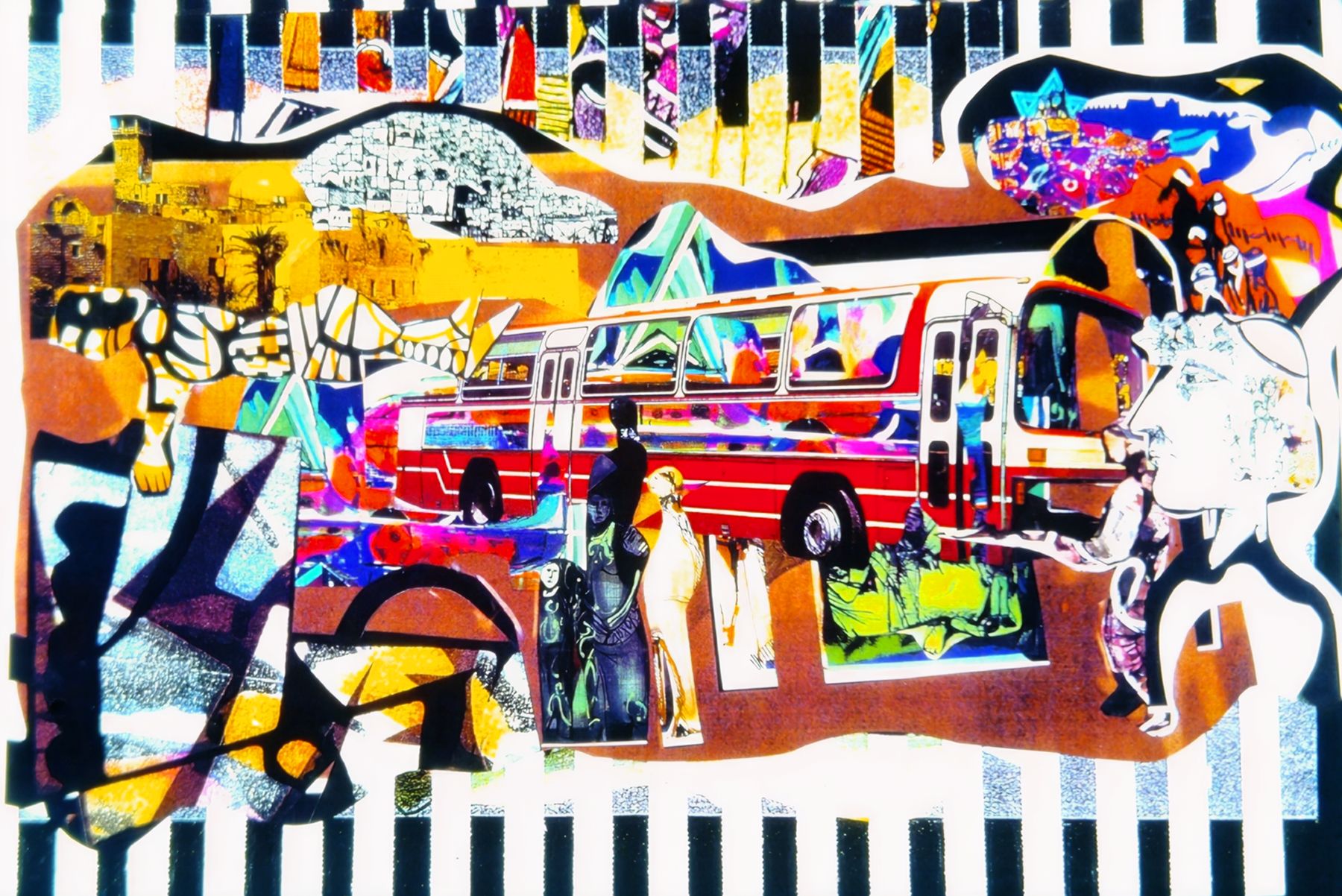

This isn't to imply that Ebgi stopped producing art; in fact, his production increased significantly. However, he diverged sharply from his conventional techniques. Instead, he spent his time creating 8.5" x 11" digital photocopies, cutting out parts from his previous works and various other media. He continually duplicated arrangements of these cutouts and replicated them using a 1990s-era Xerox office color copier.

Art appreciation is inherently subjective. The above comments on the artistic quality of Ebgi's later works reflect not their spiritual or artistic value but their marked departure from previous practices. As understanding of art evolves, there is hope that these works, produced during periods of mental incapacity, will eventually be recognized and valued more fully.

At the time, however, those familiar with his earlier work and methods were understandably distressed by his new direction. Furthermore, this approach was financially catastrophic in both severe and easily foreseeable ways.

10 | Final Days

Over time, Ebgi's mental well-being deteriorated so significantly that he was unable to function at all. Eventually, his financial resources ran out, leaving him without anything. By 2006, penniless and incapable of looking after himself, a Miami-Dade Court approved a guardianship petition after a judge adjudicated Amram incapacitated, entrusting his care toGuardianship Program of Dade County,a state-funded non-profit organization in South Florida, who arranged for him to stay in a nursing home.

Following a brief illness Amram Ebgi passed away on June 21, 2024 with his daughter by his side. Subsequently, his remains were transported to Tiberias, Israel for burial in a cemetary named Virtue Rachel (טוהר רחל)—coincidentally sharing the name of his daughter. Tiberias, a resting place for many illustrious figures of Jewish history, includingMaimonides,serves as a fitting final resting place for Amram, whose life and work traced back so often to ancient Jewish heritage.

11 | Preservation of Final Works

Fortunately for art lovers, Amram's final belongings—a small bedroom-sized collection filled with notebooks, prints, and his Trifold works—have been preserved. For nearly two decades, these items were transported among various apartments, storage units, and offices. As late as 2023, the works were housed within the corporate office of his guardians, occupying approximately 80 square feet.

By late 2023, as Amram's guardians prepared to relocate their offices, they encountered a crucial choice: either secure someone to take possession of Amram's last belongings or discard them. Fortunately, they decided to reach out to his family. His family accepted the work and it was transported from Miami to New York City, and subsequently to Los Angeles, where it presently remains.

Regrettably, Ebgi's extensive collection of etched copper plates was lost permanently. There is no documentation regarding their disappearance, but it is probable that they were sold as scrap and melted down for their copper. Each piece of artwork had its own unique copper plate, and sometimes multiple plates showing varying degrees of wear—a veritable treasure for enthusiasts of Ebgi's work, now likely lost forever.

If this site becomes unavailable in the future, you can visit our mirror at https://amramebgi.github.io.